Back سلاف غربيون Arabic Заходнія славяне Byelorussian Заходнія славяне BE-X-OLD Западни славяни Bulgarian Zapadni Slaveni BS Západní Slované Czech Westslawen German Δυτικοί Σλάβοι Greek Eslavos occidentales Spanish Lääneslaavlased Estonian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Słowianie Zachodni (Polish) Západní Slované (Czech) Západní Slovania (Slovak) Zôpôdni Słowiónie (Kashubian) Pódwjacorne Słowjany (Lower Sorbian) Zapadni Słowjenjo (Upper Sorbian) | |

|---|---|

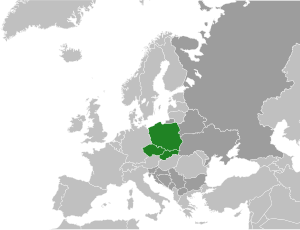

Countries where a West Slavic language is the national language Countries where other Slavic languages are the national language | |

| Total population | |

| see #Population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central Europe | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism (Poles, Slovaks, Silesians, Kashubians, Moravians, and Sorbs and minority among Czechs) Protestantism (minority among Sorbs) Irreligion (majority among Czechs)[citation needed] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Slavs |

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages.[1][2] They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries.[1] The West Slavic languages diversified into their historically attested forms over the 10th to 14th centuries.[3]

Today, groups which speak West Slavic languages include the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, and Sorbs.[4][5][6] From the ninth century onwards, most West Slavs converted to Roman Catholicism, thus coming under the cultural influence of the Latin Church, adopting the Latin alphabet, and tending to be more closely integrated into cultural and intellectual developments in western Europe than the East Slavs, who converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity and adopted the Cyrillic alphabet.[7][8]

Linguistically, the West Slavic group can be divided into three subgroups: Lechitic, including Polish, Kashubian, and the extinct Polabian and Pomeranian languages; Sorbian in the region of Lusatia; and Czecho–Slovak in the Czech lands.[9]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

GRE1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gołąb, Zbigniew (1992). The Origins of the Slavs: A Linguist's View. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers. pp. 12–13.

The present-day Slavic peoples are usually divided into the three following groups: West Slavic, East Slavic, and South Slavic. This division has both linguistic and historico-geographical justification, in the sense that on the one hand the respective Slavic languages show some old features which unite them into the above three groups, and on the other hand the pre- and early historical migrations of the respective Slavic peoples distributed them geographically in just this way.

- ^ Sergey Skorvid (2015). Yury Osipov (ed.). Slavic languages. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in 35 vol.) Vol. 30. pp. 396–397–389. Archived from the original on 2019-09-04. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ^ Butcher, Charity (2019). The handbook of cross-border ethnic and religious affinities. London. p. 90. ISBN 9781442250222.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vico, Giambattista (2004). Statecraft : the deeds of Antonio Carafa = (De rebus gestis Antonj Caraphaei). New York: P. Lang. p. 374. ISBN 9780820468280.

- ^ Hart, Anne (2003). The beginner's guide to interpreting ethnic DNA origins for family history : how Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi & Europeans are related to everyone else. New York, N.Y.: iUniverse. p. 57. ISBN 9780595283064.

- ^ Wiarda, Howard J. (2013). Culture and foreign policy : the neglected factor in international relations. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate. p. 39. ISBN 9781317156048.

- ^ Dunn, Dennis J. (2017). The Catholic Church and Soviet Russia, 1917-39. New York. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781315408859.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bohemia and Poland. Chapter 20.pp 512-513. [in:] Timothy Reuter. The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900 – c. 1024. 2000

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search